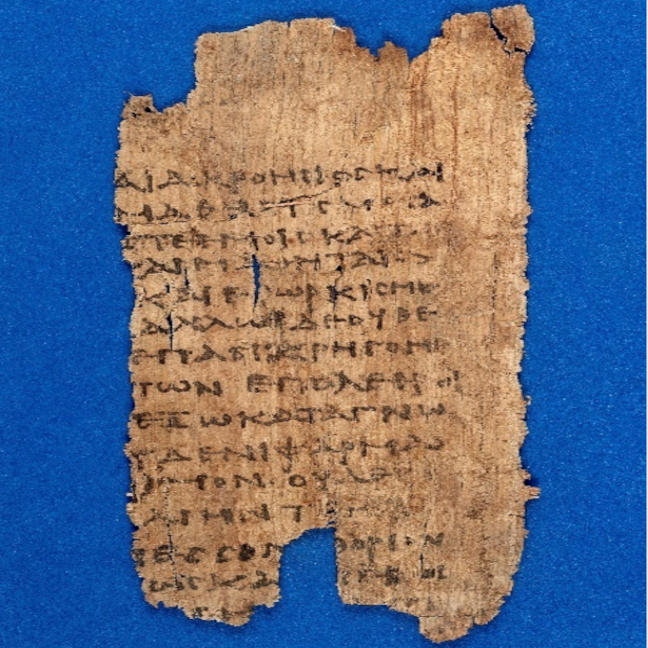

Medical professionals, by definition, do good for us. In ancient times, they affirmed the Hippocratic Oath at the start of their careers which says, in part, “I will abstain from all intentional wrong-doing and harm.” Although the Oath is no longer widely used, its spirit remains intact. Instances of unintentional harm occur and, although rare, cause great emotional and physical pain to families.

A British mother received a double mastectomy by mistake because of a translation error in her medical chart. While living in Spain, she detected a lump in one of her breasts. When her home doctor’s records were sent over and translated into Spanish, the doctors who were treating her believed that she had a family history of breast cancer. She did not, but they convinced her that the best course of action was to remove both breasts. After performing the surgery, the lump was analyzed and determined to be benign (non-cancerous). She sued the hospital for €600,000 to compensate partly for her loss.1

Medical language is precise with distinct terminology. New words occur often when a rare disease is uncovered or an emergent treatment is introduced. Along with the unique language, acronyms and abbreviations surface, some of which have more than one meaning. We believe that translations must ensure 100 percent accuracy.

A young man came into the emergency room, delirious with a headache and he kept passing out. His friends told the doctor he was “intoxicado” which became the official diagnosis on his chart and led to treatment for a drug overdose. However, in parts of the Spanish-speaking world, the word does not mean, “intoxicated”. The context is much broader and merely means that one is feeling nauseous, possibly from something they ate. Several days later, the doctors discovered that their patient had a hemorrhage which had caused the headache and resulted in a brain bleed. Because of the erroneous diagnosis and the mistreatment prescribed, he ended up a quadriplegic. His family was awarded a $71 million court settlement to help care for the patient for the rest of his life.2

Federal guidelines require hospitals to provide interpretation and translation for non-English-speaking patients to minimize the risk of complications from language barriers. Machine translations range from accuracy rates of 94 percent to a low of 55 percent, depending on the language. For example, one translation app made “You can take over-the-counter ibuprofen as needed for pain” into “You may take anti-tank missile as much as you need for pain.”3

Medical translators must be adequately trained and stay updated with the newest technology used by health care professionals for diagnosis, treatment and prognosis. Translators offer a range of expertise in medical devices and products, pharmaceuticals, medical histories, diagnosis, treatment, consent forms, and reports. In addition, knowledge of a wide range of medical conditions is critical to translating medical documents accurately. When the health and safety – not to mention the life – of a patient is of utmost importance, an experienced, qualified professional human translator is necessary. There can be no ambiguity.

To learn more, please contact Juan Lara directly at: jlara@cyphertranslations.com or +1 844-7CYPHER (+1 844-729-7437).

For more information, please visit our website at https://cyphertranslations.com

Artwork: Piece of original papyrus with Hippocratic Oath. Photo Credit: Conrad et al, The Western Medical Tradition 800 BC to AD 1800 (1995) Fig. 3, p. 21

1Retrieved 27 January 2022 from Medical Translation Gone Wrong: 7 Devastating Medical Translation Errors (k-international.com)

2Source: Health Affairs Retrieved 27 January 2022 from Language, Culture, And Medical Tragedy: The Case Of Willie Ramirez | Health Affairs

3Source: UCLA Medical Center, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.